Book Review: A Giacometti Portrait by James Lord

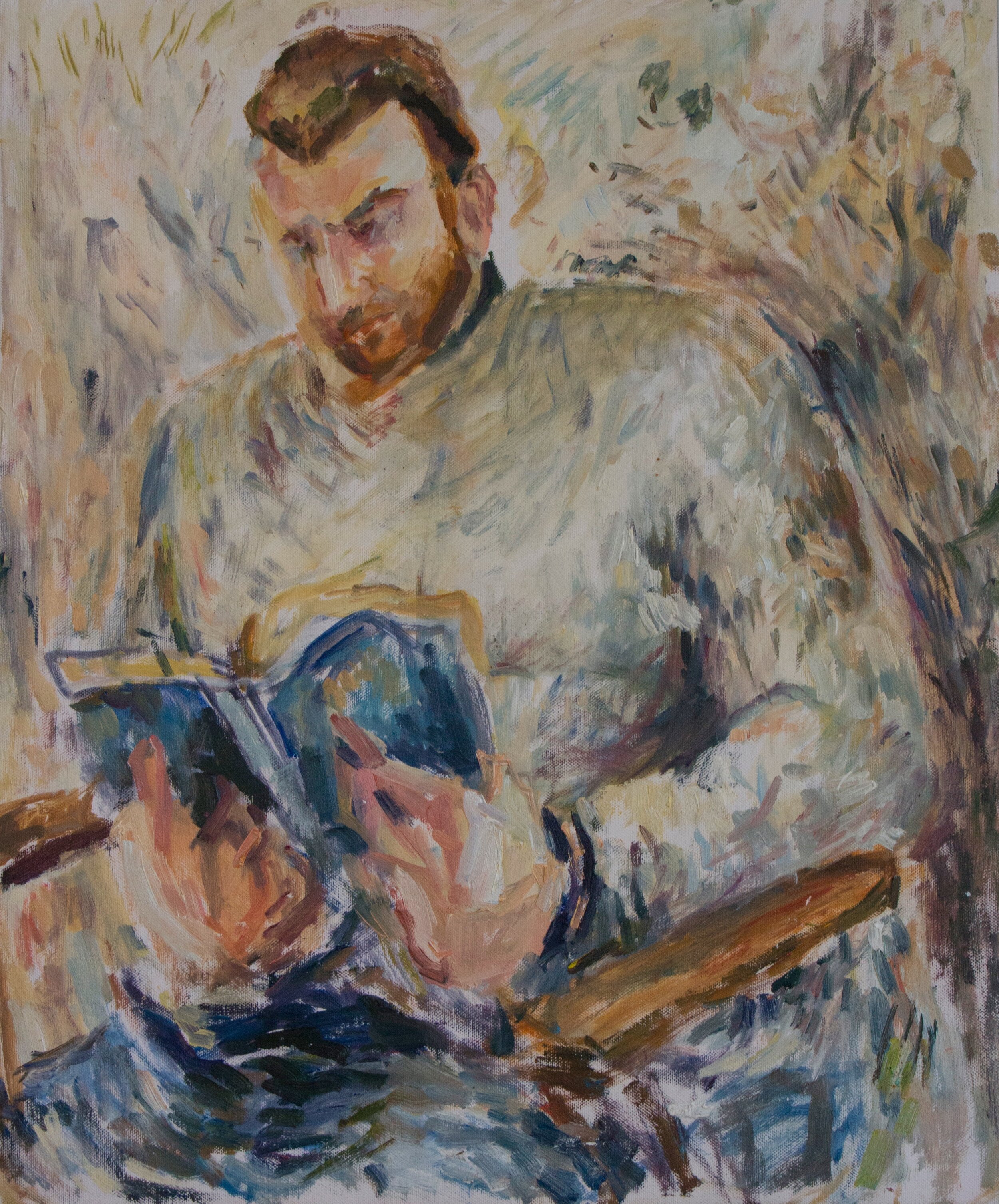

I first read this quick book for a school assignment as a way to engage in the process and painting of Albert Giacometti. The book follows the author, James Lord, as he sits for his friend Giacometti, already considered one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century at the time. The story begins as Lord agrees to sit for Giacometti for a one-session “quick portrait sketch on canvas” (3). When the initial session ends, Giacometti realizes it’s too late to stop: he must continue with the work as a full painting. Lord ends up sitting for a total of eighteen sessions (the book is divided into a chapter for each session), delaying his flight out of Paris multiple times solely for the purpose of sitting for the portrait.

What ensues are various discussions between Lord and Giacometti ranging from art to the best way to die or simple chit chat, but what emerges from their, at times seemingly insignificant exchanges, is a discussion of Giacometti’s primal motivation for creating (he often interchanges between sculpting and painting as we see in the book). Much like the portrait as we follow in its evolution, Giacometti’s emotions towards making art vacillate between frequent optimism and, even more frequently, lows as he paints. He goes from untiring efforts to press forward to being on the verge of quitting art altogether and back again to hope. Underlying all this is the importance he places on pursing vision of reality and the recognition that art ultimately fails to true capture reality as we see it. Lord writes:

What meant something, what alone existed with a life of its own was his indefatigable, interminable struggle via the act of painting to express in visual terms a perception of reality that had happened to coincide momentarily with my head. To achieve this was of course impossible, because what is essentially abstract can never be made concrete without altering its essence.” (72)

It is this hope of grasping at reality through painting that spurs Giacometti forth in his painting and the very fact of its impossibility that provides his eternal despair. It is perhaps because of this paradox that Giacometti creates his work, as Lord writes, “almost a by product [. . .] of his endless struggle” (97).

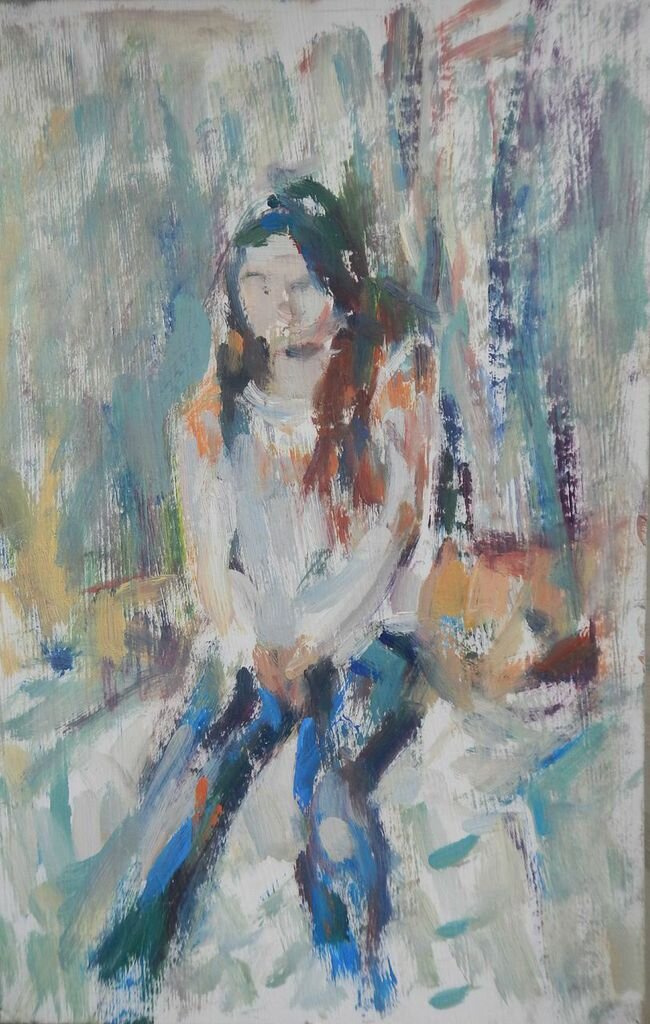

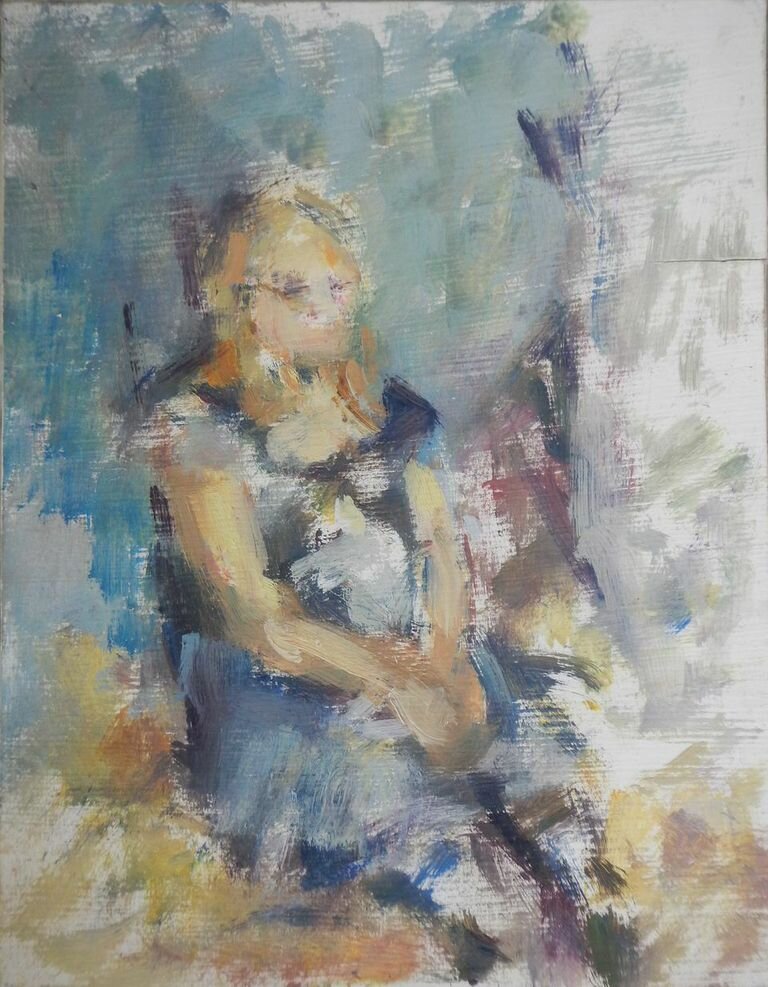

Though we find the ebb and flow of this struggle at the heart of the book, the book touches on several over notes, several of which I found especially intriguing in thinking of it in relation to my own work as an artist. For example, Lord writes about how painting for Giacometti requires that he see his subjects as though for the first time, “To him [. . . ], the visual response to reality was utterly new, because he possesses the rare capacity of seeing a familiar thing with the intense vividness of completely new sight.” (48) It is this ability, Lord believes, that imbues Giacometti’s work with a sense of freshness and newness. In my own work, I find that this prevents me from get stuck painting a subject with a particular approach or technique and allows me to take risks. Likewise, their discussion of what makes a person recognizable rings true:

“But there is very little differences between people. For instance, what causes me to recognize you in the street?”

“The ensemble?”

“Yes, but not any single detail. Details are unimportant in themselves.” (40)

Often we get caught up thinking creating a likeness in portraiture is about the features and details of their face rather than focusing on the whole of the person and how he or she is situated within space. In Giacometti’s on work, we can see how he always painted with the full figure, even though he always focused the greatest attention on the volume of the head.

If one can humor the numerous tirades and complaints of Giacometti that accompany his creative process and submit to the subjective viewpoint of our sitter, then one can indeed find a quick, one sitting read that gives birth to a new or deeper appreciation for the artist even if one is not naturally inclined towards his work. It proves to be not simply a narrative of Giacometti’s process for a portrait, but a portrait of Giacometti himself.

Lord, James. A Giacometti Portrait. Farrar Straus Giroux, 1980.